Can changes in our lives evoke changes in our language patterns? In my BA thesis, I’m looking at young speakers who – at the time of the sociolinguistic interviews – were students at university. This stage of life is called emergent adulthood and is often associated with instability and changes, for example in an individual’s social environment, in their workplace, or regarding their socioeconomic status. In previous research on language change, emergent adulthood has only been investigated scarcely because it was assumed that speakers stay stable in their linguistic patterns after puberty. However, studies have shown that language change can in fact occur after this assumed stabilisation.

Can changes in our lives evoke changes in our language patterns? In my BA thesis, I’m looking at young speakers who – at the time of the sociolinguistic interviews – were students at university. This stage of life is called emergent adulthood and is often associated with instability and changes, for example in an individual’s social environment, in their workplace, or regarding their socioeconomic status. In previous research on language change, emergent adulthood has only been investigated scarcely because it was assumed that speakers stay stable in their linguistic patterns after puberty. However, studies have shown that language change can in fact occur after this assumed stabilisation.

The data for my thesis consists of a panel of six young speakers who were interviewed twice. First, they were interviewed at the age of 19/20, when they had just started studying. Then, five years later, they had (almost) finished their studies at university and were interviewed again.

Looking at the FACE vowel

For the analysis, I look at the way the speakers realize the FACE vowel in words such as face, gate, and bay. This phonetic variant is well researched in the North East of England and two major changes have been reported on in previous research: On the one hand, younger speakers are expected to realize face as [fe:s]. This monophthongal realization is associated with a supralocal general Northern identity. On the other hand, a shift towards the “standard English” closing diphthong has been observed, which means that speakers produce face as [feɪs]. This, too, characteristically represents a shift away from traditional and local forms, especially of younger speakers. These traditional and local realizations of FACE such as in-gliding diphthong [ɪe] are lost.

For the analysis, I look at the way the speakers realize the FACE vowel in words such as face, gate, and bay. This phonetic variant is well researched in the North East of England and two major changes have been reported on in previous research: On the one hand, younger speakers are expected to realize face as [fe:s]. This monophthongal realization is associated with a supralocal general Northern identity. On the other hand, a shift towards the “standard English” closing diphthong has been observed, which means that speakers produce face as [feɪs]. This, too, characteristically represents a shift away from traditional and local forms, especially of younger speakers. These traditional and local realizations of FACE such as in-gliding diphthong [ɪe] are lost.

In my analysis, I attempt to find out in how far the speakers’ choices in regard to the FACE vowel change or stay stable throughout their lifespan. While investigating FACE, I also take constraints such as following sounds and word frequency into account.

Social changes and who you speak to make a difference

The results of my analyses support previous findings of a trend towards the supralocal monophthong (Watt 1999, Watt 2002). However, differences between male and female speakers are rather apparent. While the female speakers stay relatively stable in their realisation of FACE, three out of four female speakers predominantly using the monophthong, the two male speakers significantly shift from one preferred realisation in the first interview to the other way of producing FACE in the second interview.

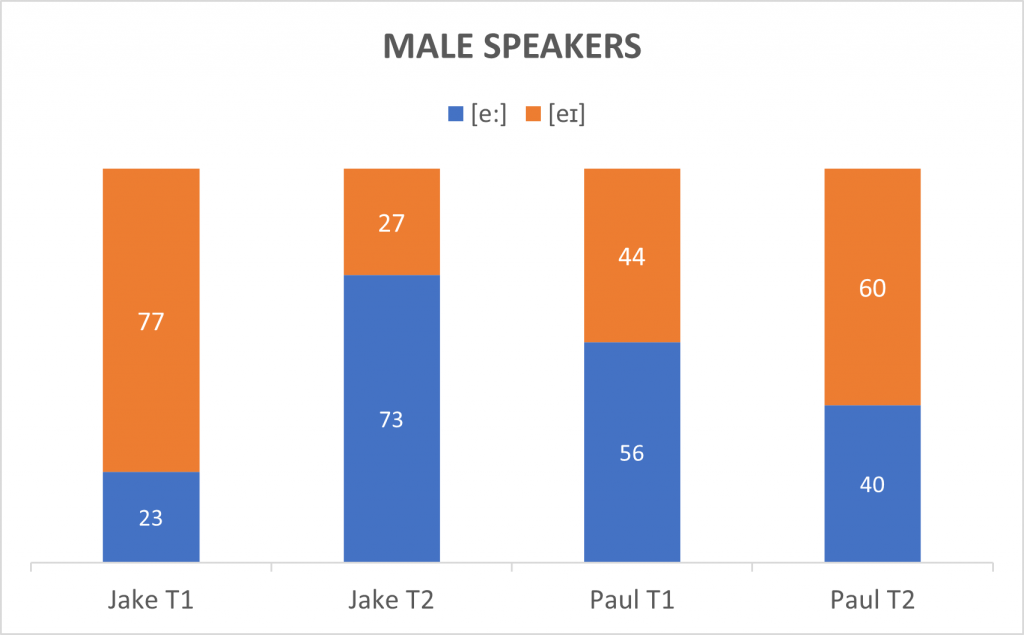

The following graph shows my overall results for the male speakers. Jake finished his post-graduate and is now working as a project manager. While starting off as predominantly diphthongal, he shifts to a more monophthongal realisation of FACE, which could be a result of work place pressure as he is working in a local company. In the North East, local dialects are often taken with pride in these local workplaces. On the contrary, Paul already starts off with a rather variable realisation of FACE in 2009. After his studies, he has been struggling with finding a secure workplace. This could be a reason for him being linguistically variable, and perhaps accommodating to his interview partner Amelia’s way of speaking (her being stable in her diphthongal realisation) during the second interview.

Put into a nutshell, the findings of my BA thesis support the assumption that language change can indeed occur after critical age, i.e. after puberty, and that especially the instable age of emergent adulthood heavily influences speakers‘ dialect in relation to the trends in their speech community.