We can trace how the grammar of a language varies in speakers and across time by looking at changes in sentence and word structure. These (types of) changes sometimes imply that different grammatical constructions can co-exist.

To give an example, in English as it is spoken today, the following three utterances express the exact same thing – that somebody possesses something. They are called “stative possessives”:

1) I have a cell phone.

2) I’ve got a cell phone.

3) I got a cell phone.

From a sociolinguistic point of view, however, these different ways of saying the same thing also carry different social meanings. They can be indicative of the speaker’s age, profession, social class, gender, or origins – got, for instance, is associated with U.S. American English. Depending on the word which precedes or follows the stative possessive, different forms are more frequent i.e., when the subject refers to something or someone specific, then speakers choose mostly have got (e.g., “I’ve got a friend over there”). Therefore, variation in stative possessive use seems to correlate with both social and language-internal factors.

Analyzing diachronic oral data

My MA thesis relies on a panel sample consisting of six informants from Tyneside in the North-East of England, who were first interviewed in 1971 shortly after they had entered the workforce. Forty-two years later, the same speakers were re-recorded during their retirement. With these panel data, I investigate variability in an individual speaker’s grammar throughout the course of their lives.

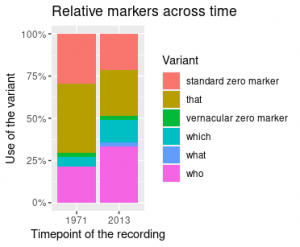

I investigate three variables: relative pronouns, general extenders and the system of stative possessives. Relative pronouns include the standard forms which, that, who and the zero marker, which functions as the object of the sentence (e.g., “I had a tape a tape Ø I used to follow”). I look at the two vernacular variants what and the zero relative as well, which is the subject of the relative clause (e.g., “There’s only two people Ø had a telephone”).

General extenders are used at the end of a speaker’s utterance (e.g., “They had like cottages and that”).

The system of stative possessives makes speakers choose between the three forms previously mentioned.

In order to compare the individual linguistic choices, I explore how often the six panel speakers use one variant or the other, and whether their choices change over time (1971-2013). I also want to find out to what extend/how linguistic environments as well as social meanings influence the informants’ grammars.

Diachronic versus synchronic findings

Looking at all panel speakers together, we can see that two major changes occur between the first and the second interviews. The plot below shows that they have increased their use of which, who and what, whereas that and the standard zero marker are produced less frequently in 2013 than in 1971. Just like previous research, my findings document that linguistic mechanisms might be at work. In particular, who has become increasingly categorical where the previous word is an animate subject (e.g., “There was a guy who was a ex-commander”).

Click on the picture to see the plot!

The findings also indicate that the most predominant general extender is and that. And that is mainly produced by the three working-class speakers of the panel. This pattern of social class variation has also been reported by literature focusing on community trends. It can be argued that the overall use of specific variants relates to the stratum of society.

With respect to the system of stative possessives, the six informants make linguistic choices in their old age just like the rest of their speech community. They use have got and got much more often and reduce the production of have. The form have got appears to occur especially with subjects that contain specific references (e.g., “We’ve got a house from when we were brought up”). Nonetheless, one of the panel speakers, Fred, has not adopted the incoming variant got by 2013. A possible explanation why Fred does not follow the overall trend might be his presentation as a conservative teacher in the second interview.

The overall results of my longitudinal study give insight into how the six panel speakers behave regarding their speech community. My diachronic findings support the claim that grammatical variation does not only depend on the linguistic context but also on the speakers’ differences in social traits/characteristics.

I'm wondering whether your Tynesiders actually had "cell phones" (AE) rather than mobiles (BE)?

Thank you for your question! In this case our speaker indeed uses "cellphone" – it would be interesting as a separate study to check which phrase different people use, and if this changes over time!